(Source)

(Source)

| Website: | no page found |

| Facebook: | no page found |

| Email: | no email found |

| Landline: | no number found |

| Mobile: | no number found |

| City/Municipal: | Gitagum |

| Barangay: | Poblacion |

| Address: | Cagayan-Iligan Hiway |

| GPS Location: | |

| more Info: | |

(Source)

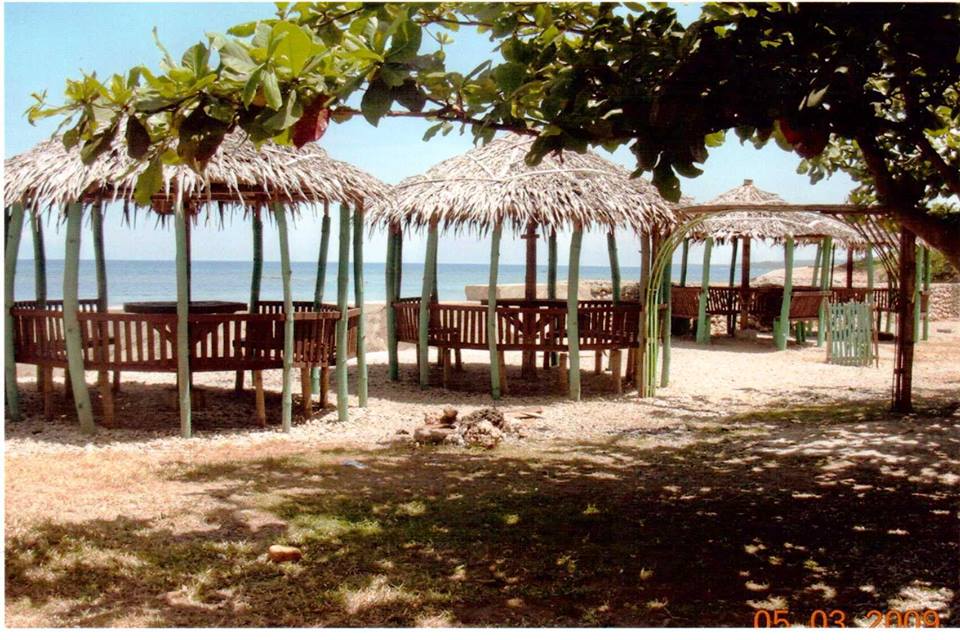

Quiet and peaceful small, Japanese/Filipina owned resort, where you can enjoy you lunch and the fresh sea breeze.

Entrance Fee: Php 30.00 — adult

Php 10.00 — kids ( 6-12yrs )

SPECIAL PACKAGE DEAL IS AVAILABLE TO CORPORATE EVENTS

(Source)

| Website: | no page found |

| Facebook: | no page found |

| Email: | no email found |

| Landline: | (88) 555 0366 |

| Mobile: | 0923 840 8337 |

| City/Municipal: | Gitagum |

| Barangay: | Burnay |

| Address: | Cagayan-Iligan Hiway |

| GPS Location: | |

| more Info: | |

(Source)

| Website: | no page found |

| Facebook: | Ocean View Beach Resort |

| Email: | no email found |

| Landline: | |

| Mobile: | 0916 361 5706 0926 320 7136 |

| City/Municipal: | Gitagum |

| Barangay: | Burnay |

| Address: | Cagayan-Iligan Hiway |

| GPS Location: | |

| more Info: | |

(Source)

| Website: | no page found |

| Facebook: | |

| Email: | no email found |

| Landline: | |

| Mobile: | |

| City/Municipal: | Gitagum |

| Barangay: | Matangad |

| Address: | |

| GPS Location: | |

| more Info: | |

(Source)

(Source)

Gitagum is one of the places that celebrate Sinulog Festival every third Sunday of January. Cebu City is known for this festive celebration. The Sinulog Festival is in honor of the Santo Nino or the Child Jesus, who is represented by an image that devotees consider miraculous.

| Website: | no page found |

| Facebook: | no page found |

| Email: | no email found |

| Landline: | no number found |

| Mobile: | no number found |

| City/Municipal: | Gitagum |

| Barangay: | |

| Address: | no street address found |

| Google Map: | |

(Source)

(Source)

No other info at this time. Research in progress.

| Website: | no page found |

| Facebook: | no page found |

| Email: | no email found |

| Landline: | no number found |

| Mobile: | no number found |

| City/Municipal: | Gitagum |

| Barangay: | Gregorio Pelaez (Lagutay) |

| Google Map: | |

“At the foot of the cliffs is a cave that the local’s call “Piri’s langub” or Piri’s cave. While its opening can barely allow a small kid to climb in, the length of the cave system is said to extend to the neighboring town of Mauswagon a few kilometers away connecting to another opening out to sea.” (Source)

|

by Arnold P. Alamon In the sleepy municipality of Gitagum a few minutes away from the new Laguindingan airport is Barangay Tala-o. The settlement stands like a fortress. It is hoisted 200 feet up by a solid limestone base and according to the locals, the area has no history of landslides. Proof of its underwater past are the calcified corrals that jut out from the landscape. But through the geologic work of time, it is now a good kilometer away from the shore. Its elevation and distance make it safe from the unpredictable temper of water. When one stands on the edges, the view is that of the sea, Camiguin Island in the distance, and just recently the sight of airplanes landing and taking off. At the foot of the cliffs is a cave that the local’s call Piri’s Langub or Piri’s cave. While it’s opening can barely allow a small kid to climb in, the length of the cave system is said to extend to the neighboring town of Mauswagon a few kilometers away connecting to another opening out to sea. Local folklore tells of the generous Piri, a dili ingon nato (one who is not like us) who supposedly inhabits the cave located at the entrance to the settlement. The entity serves as the benefactor and guardian of the residents of Tala-o. When residents prepare for wedding and feasts, story has it that they place offerings of food and on pieces of paper they scribble their requests for plates and silver at the mouth of a cave. When the townsfolk come back a day or two later, waiting for them are stacks of ceramics and silver as requested. This example of a Founder’s Cult, an anthropological constant in various cultures, reveal the belief in a negotiated relationship between non-human entities that are supposed to inhabit and own elements of the environment and the temporal humans who seek to share the space with them. Nature in these cases assume a supernatural form such as the good encanto Piri. How the local people regarded him is an indication of the kind of contractual relationship people used to have with nature and their environment. These types of belief which are prevalent in Filipino folklore reveal the indigenous disposition towards their surroundings. It is one defined by a deep respect and reverence for nature for the bounty she offers and it is also one that is marked by clear boundary markers for she can also bring misfortune and disasters when lines are crossed. Apart from Piri, there are other entities, this time less benevolent and more evil in disposition, that inhabit the community environs according to the local folklore of Tala-o. A kapre or half-horse, half-human giant is said to inhabit a huge balite tree also on the same row of cliffs as Piri’s cave. Another encanto resides in another balite tree also on the same row further to the East. Standing guard like sentries of a tower, these elements in the local folklore can be interpreted as boundary markers of the community demarcating territory that is inhabited by humans, therefore tamed on the one hand; and territory that belongs to the dili ingon nato or is wild and dangerous, on the other. But these tales of Piri, kapres, and encantos are fast losing currency among the younger generation of Tala-o residents. Many of them have left “the fortress” to settle on the roadside a kilometer down when the highway was constructed decades ago. It has since then became more populous and gained for itself a separate political jurisdiction as the Barangay of Burnay. These curious stories may remind us of the tales our elders and manangs told to us as children during brownouts and the moon was full. But more than serving as a cautionary tale for naughty boys and girls to keep close to home, embedded in these narratives are indigenous and local knowledge that are actually valuable to the contemporary life of the community especially as it responds to disaster risks and climate change. In an ongoing exploration on the uses of indigenous knowledge in disaster risk reduction and climate change adaptation, UP anthropologist Chim Zayas is investigating the location of ancient Japanese shrines along an exposed fault line in the island of Awaji, Japan. A massive earthquake devastated the island in 1995. Her theory is that the Japanese ancestors who built shrines for the guardian diety of the land as well as for the malevolent diety for fire must have been aware of the danger posed by the fault line. In this instance, the shrines served as boundary markers between human settlements and the potential source of natural hazards such as the fault line. From an anthropological sense, this is similar to the dili ingon nato in communities like Tala-o. Piri, kapres, and encantos and their location are markers of a community’s danger zones giving credence to the idea that local indigenous knowledge has much to share in our contemporary efforts to mitigate the effects of natural hazards. Last December 2012, typhoon Pablo ravaged the island of Mindanao, crossing through the heartland and exiting by way of Misamis Oriental. The eye of the storm passed over Barangay Tala-o but its inner and outer wall felled trees and blew away roofs. However, in Barangay Burnay, the force of the winds created 20 foot high waves in a storm surge that threatened to destroy homes along the highway and near the shore. Perhaps heeding the native call of the benevolent encanto to climb the fortress of their former abode, the residents of Burnay sought shelter and found safety atop Piri’s grand limestone cliffs. |

The two cave sites in Gitagum are located on a cleared land

and cultivated field.

They are coral-line caves, located about 20m from each other.

Both caves have bare vegetation and low canopy cover.

Soil substrate is dry without guano deposit. The caves were

extensively disturbed. Burning of firewood was observed.

(Source)

| Website: | no page found |

| Facebook: | no page found |

| Email: | no email found |

| Landline: | no number found |

| Mobile: | no number found |

| City/Municipal: | Gitagum |

| Barangay: | Matangad |

| Google Map: | |

Dako na Ilihan (big natural fortress)

The ilihans or natural fortresses in Initao were believed to be used even before the Spaniards came to the district. Ms. Vismin Lozano, a Higaunon and former Department of Interior and Local Government of Initao, narrated that these natural fortresses were the refuge of the women and children of Higaunon, the earliest known settlers of Initao, when raiders would attack their community. According to their local history there were constant battles waged between the Moro and the Higaunon. Ilihans were used as the primary strategy of the Higaunon to protect their community. Ms. Lozano mentioned that Spaniards later used these natural fortresses to build clay bricked-watchtowers as these hills make perfect vantage points to see the arrival of people both by water and by land. Today, the Dako nga Ilihan is now privately owned by the current mayor of Initao, Mayor Enerito Acain V. The Mayor plans to make the large natural fortress a historical tourist spot by 2016.

Dako nga Ilihan is a large hill, surrounded by heavy forestation, at a location that overlooks the sea to the west. The site also has a vantage point of Gamay nga Ilihan to the north. To get to the site, one must walk a 30-minute to 1-hour trek from the sentro of the town to reach the top of the hill. (Source)

The site is on private property

Gamay na Ilihan (small natural fortress)

The site is a hill located beside the Initao River.

See description on Dako na Ilihan

(Same location as Dako na Ilihan)

The site is on private property.